The starting text for this

anagram is a section from the essay on Mt. Fuji in Exotics and Retrospective

by Lafcadio Hearn, an Irish writer who spent his last 14 years in the late 1800's

living in Japan, and is well-known for his writings about that country. This

is from section 6 of the essay "Fuji-no-yama" (whose entirety can be found

here) and tells the

story of one particular couple's adventure with the mountain, in the context of the

tale of Hearn climbing the mountain himself.

Below that is an anagram of this text into nine poems (one, #4, being a short

retelling of Hearn's story) inspired by nine images from Hokusai's famous series

of woodcuts, the Views of Mt. Fuji. Each poem is shown with its

accompanying image.

Squatting by the wood fire, I listen to the goriki and the station-keeper

telling of strange happenings on the mountain. One incident discussed I remember

reading something about in a Tokyo paper: I now hear it retold by the

lips of a man who figured in it as a hero.

A Japanese meteorologist named Nonaka attempted last year the rash

undertaking of passing the winter on the summit of Fuji for purposes of

scientific study. It might not be difficult to winter upon the peak in a

solid observatory furnished with a good stove, and all necessary

comforts; but Nonaka could afford only a small wooden hut, in which he

would be obliged to spend the cold season without fire! His young wife

insisted on sharing his labors and dangers. The couple began their

sojourn on the summit toward the close of September. In mid-winter news

was brought to Gotemba that both were dying.

Relatives and friends tried to organize a rescue-party. But the weather

was frightful; the peak was covered with snow and ice; the chances of

death were innumerable; and the goriki would not risk their lives.

Hundreds of dollars could not tempt them. At last a desperate appeal was

made to them as representatives of Japanese courage and hardihood: they

were assured that to suffer a man of science to perish, without making

even one plucky effort to save him, would disgrace the country; - they

were told that the national honor was in their hands. This appeal

brought forward two volunteers. One was a man of great strength and

daring, nicknamed by his fellow-guides Oni-guma, "the Demon-Bear," the

other was the elder of my goriki. Both believed that they were going to

certain destruction. They took leave of their friends and kindred, and

drank with their families the farewell cup of water - midzu-no-sakazuki

- in which those about to be separated by death pledge each other. Then,

after having thickly wrapped themselves in cotton-wool, and made all

possible preparation for ice-climbing, they started - taking with them a

brave army-surgeon who had offered his services, without fee, for the

rescue. After surmounting extraordinary difficulties, the party reached

the hut; but the inmates refused to open! Nonaka protested that he would

rather die than face the shame of failure in his undertaking; and his

wife said that she had resolved to die with her husband.

Partly by forcible, and partly by gentle means, the pair were restored

to a better state of mind. The surgeon administered medicines and

cordials; the patients, carefully wrapped up, were strapped to the backs

of the guides; and the descent was begun. My goriki, who carried the

lady, believes that the gods helped him on the ice-slopes. More than

once, all thought themselves lost; but they reached the foot of the

mountain without one serious mishap. After weeks of careful nursing, the

rash young couple were pronounced out of danger. The wife suffered less,

and recovered more quickly, than the husband.

The goriki have cautioned me not to venture outside during the night

without calling them. They will not tell me why; and their warning is

peculiarly uncanny. From previous experiences during Japanese travel, I

surmise that the danger implied is supernatural; but I feel that it

would be useless to ask questions.

The door is closed and barred. I lie down between the guides, who are

asleep in a moment, as I can tell by their heavy breathing. I cannot

sleep immediately; - perhaps the fatigues and the surprises of the day

have made me somewhat nervous. I look up at the rafters of the black

roof - at packages of sandals, bundles of wood, bundles of many

indistinguishable kinds there stowed away or suspended, and making queer

shadows in the lamplight. . . . It is terribly cold, even under my three

quilts; and the sound of the wind outside is wonderfully like the sound

of great surf - a constant succession of bursting roars, each followed

by a prolonged hiss. The hut, half buried under tons of rock and drift,

does not move; but the sand does, and trickles down between the rafters;

and small stones also move after each fierce gust, with a rattling just

like the clatter of shingle in the pull of a retreating wave.

[1]

Fuji's perfect outline points heavenward

near the river's mouth.

The firm peak in the warm sky

paints across the lake an odd reflection,

with dirt draped in snow

rather than brown land almost up to the top.

Perhaps the elder pedagogue of Edo

is making a subtle point.

The old boatman of Kai

rowing to the tranquil village there

And the middle-aged Buddhist

who once pined for youthful times

Endorse this bitter truth:

Seen on reflection, things are often changed.

[2]

Summer at midday.

The deck of a tea house on the tan road to Kyoto

is almost full of men and women.

Two brusque men work on their master's carriage.

Two others pause for a nap.

A courtesan demands her favourite drink,

adding quite haughtily

"That you are tired does not matter to us."

Only one heeds with kind regard

the voluptuous plain,

Mount Fuji on the horizon,

the cities beyond.

A group which imitates the leaders

of certain nations today.

[3]

The gifted artist devoted this panel to a

scene

that evokes the refined tea-house tableau

but is, we deduce with careful study,

almost the opposite.

The building is bigger, grander:

not a house of commerce and commotion

but a noiseless temple of silent sanctuary.

Nearly everyone is staring at the fine view of Fuji.

The small girl, her view of the vista blocked,

ponders the old riddle:

If a peak dwells in the distance

but is hidden, does it exist?

[4]

Footsteps go east.

Two sufferers, a weatherman and his wife,

hunker down to run through hueless snow

on the dead, lifeless, ice-bound turf

back to their little hut on the dew-fogged top

of Edo's storied mount.

Inside, a buttercup flower

in a kettle on a naked table:

the third thing in danger

of being dead before the cherry blossoms break.

Death before dishonor is their shared motto.

(If politicians followed that rule

only about seventeen

would remain breathing today.)

[5]

Gray-tinted clouds befogging the base

are fouled with piercing zigzags of pure white

as heavy rain runs down slopes to the basin below.

The peak tries hard to stay unspoilt,

but it may or may not;

The mountain does not speculate,

nor the awful deluge.

Hidden from view,

a wealthy samurai bows his head,

rebukes in gruff tones

the rough path his feet walk upon

then thinks a while.

The round ruddy sun sets,

painting his mountain's profile fiery red.

[6]

A large conifer claims its dominance

in the center of this oddly phallic vista.

Below, curious men attempt to measure its girth,

encircling its woody body beneath

the dense timber and rugged matter,

even as protruding pine needles and offshoots

scratch and hurt them.

Up there in the heated canopy

blue birds live with the quail

in nests made of new shoots;

Chaos, pain, weapons, or mythological dragons are not found.

While at the severe woodland's leafy bottom,

everything is weighty.

[7]

The tired fisherman perches there

on the cramped rock, holding four lines

in the turgid updraft of water

that lashes and breaks unto the shore.

A small figure (son or daughter, perhaps)

holds a basket of surf clams, tuna, damp cereals:

their nutriment for the coming days of heavy work

with plow and web and cogged wheel.

So in accord with nature

are the widower and kid

they fail to notice how often their tableau

imitates that renowned formation,

Mount Fuji.

[8]

Going west on Tokaido Road

seven humpbacked travelers are beset

with a sudden gust of wind

that sweeps down the highway,

scattering papers here and there

under gray leaves which fly through the air like dead fowls.

Outwitted and confused by

the drama of streams and currents taking place there

no one even notices this:

The papers that hold the weighty writings of

The Great Teacher,

once believed to be so classic and essential,

are blank as the face of Fuji.

[9]

Pinnacles are rarely reached easily.

Ever since the master drew this great water scene,

all waves are expressed

(knowingly or not)

by how they match

its rugged nucleus of foam and fluid.

Mad men in miniature schooners go by,

Heaved on fat swells high up in the air

then (ebb inevitably pursuing flow) earthward.

Shipmates cast off dire hopes.

Quiet pervades the peak.

As dusk falls like a knitted blanket

we apprehend Fuji's rueful theme:

Summits easily reached rarely are pinnacles.

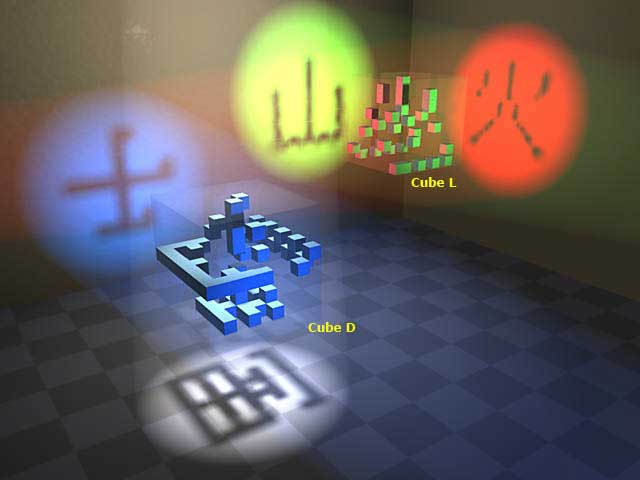

In addition to being an anagram, the construction of these poems (each having exactly 81 words) was governed by another constraint, which is revealed by applying this procedure to each of the nine poems:

- Arrange the poem's 81 words in a 9x9 square, in the obvious way: by writing the words, in order, in 9 lines of 9 words each.

- Make a 9x9 grid of numbers, Grid D (for Divisibility), where each cell has the number "1" if the sum of the letter values in the corresponding word (using A=1, B=2, C=3 etc.) is exactly divisible by 9, or "0" if it is not.

- Make another grid of numbers, Grid L (for Length), with a "1" in each cell if the corresponding word has exactly nine letters, or "0" if it does not.

(Note that the rules for Grid D and Grid L are both based on the number 9, in keeping with the theme of nineness.)

For example, here are the grids for the final poem:

GRID D (the 1's mark

the locations of the words with letter-sum divisible by 9)

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0

0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

GRID L (the 1's mark the locations of the 9-letter words)

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

Next, form Cube D and Cube L by stacking the grids for the nine poems - poem #1 on top, #2 directly under it, then #3, and so forth. Imagine building Cube D and Cube L (each being a 9x9x9 arrangement of 729 small cubes) out of physical materials, with the following rule: a small cube labelled "0" is made with transparent glass, a "1" cube with solid wood.

Now for the final step. Suspend Cube D and Cube L in a room and shine four beams of light at them: from the top and right onto Cube D and from the front and right onto Cube L. The shadows cast by the cubes on the walls and floor are shown in the picture below, which was created using a computer graphics model of the two cubes:

The shadows make reasonable renderings of four Japanese Kanji characters which are especially pertinent to the anagram:

The red shadow is the symbol for fire.

The green shadow is the symbol for mountain.

Put together, these make the compound Kanji symbol

("fire-mountain") for volcano.

The white shadow is the symbol for wealth, pronounced FU

The blue shadow is the symbol for samurai, pronounced JI

Put together, these make the compound word Fuji, the name of

the mountain.